Understanding Archival Scholarship in a Digital World

In the twenty-first century, historical scholarship and literary research have entered a new era of accessibility. What once required a journey to a dimly lit reading room or an exclusive archive can now often be done online, through carefully digitized repositories, university collections, and digital archives. Yet with this convenience comes a challenge: how do we cite manuscripts, letters, and other unique materials responsibly and transparently in academic writing?

The Modern Language Association (MLA) provides one of the most flexible and comprehensive frameworks for citing such materials. MLA’s ninth edition (2021) recognizes the diversity of modern research sources, from handwritten correspondence to born-digital documents. Its approach to archival citation emphasizes accuracy, provenance, and retrievability—ensuring readers can locate the exact item being referenced, whether in a physical box or a digital folder.

Archival materials are distinct from books or journal articles because each item is unique: a single letter, an annotated draft, or an unpublished photograph may exist nowhere else. Digital archives amplify this uniqueness, offering scans or transcriptions that can differ in metadata, pagination, or editorial treatment. For this reason, MLA style encourages a “layered citation” model—where each element (item, collection, institution, platform) is cited in order of relevance, separated by periods.

The purpose of this essay is to explore how MLA style applies to archival and manuscript materials, both physical and digital. It will discuss general principles, digital-era challenges, and specific examples of citations for letters, translations, and hybrid collections. The essay will also offer a comparative table summarizing core MLA components and best practices for modern researchers.

Core Principles of MLA Archival Citation

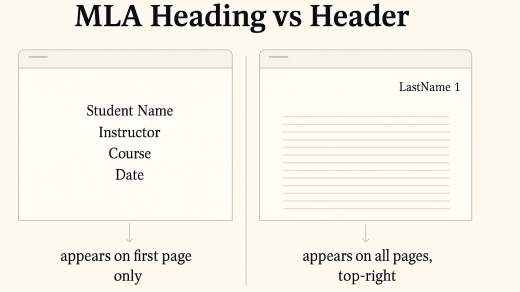

Archival citation in MLA style follows the same logic as any source: provide enough information for a reader to locate the item. However, archival materials often require additional contextual data because they are housed within collections that contain thousands of items. MLA guidelines recommend four primary elements:

-

Description of the item – Identify the type of material (letter, diary entry, manuscript draft, photograph, etc.) and to whom or by whom it was created.

-

Title or description in quotation marks or italics – Use quotation marks for individual items; italicize the name of the larger collection or digital archive.

-

Container elements – Specify the collection title, series, box and folder numbers, repository name, and physical or digital location.

-

Optional elements – Include dates of creation, URLs, DOIs, access dates, or call numbers if relevant.

Example 1: Manuscript Letter (Physical Archive)

Austen, Jane. Letter to Cassandra Austen, 5 March 1814. Jane Austen Papers, Add. MS 70623, British Library, London.

This citation begins with the author’s name and the item’s title, followed by the collection, the manuscript identifier, and the institution. It omits the word “collection” because MLA treats such descriptors as part of the container information.

Example 2: Digitized Manuscript

Woolf, Virginia. Diary, 1915–1919. Virginia Woolf Collection, New York Public Library Digital Collections,

digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-d8df-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. Accessed 12 June 2025.

Here, the digital archive replaces the physical repository. The URL and access date confirm retrievability.

Example 3: Letter in an Edited Online Collection

Du Bois, W. E. B. “Letter to Walter White,” 2 Apr. 1931. Digital Schomburg: Correspondence Files, New York Public Library,

digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/…

The MLA’s adaptability allows scholars to cite both the material and the digital platform hosting it. The use of italics for Digital Schomburg signals that it is the collection (the container), while the letter is the specific item (the core source).

MLA also accommodates translated or transcribed materials—common in digital archives. In such cases, it is ethical to distinguish the original author from the translator, editor, or curator responsible for the digitized form.

Example 4: Translated Letter

Kafka, Franz. Letter to Milena, translated by Mark Harman, Digital Franz Kafka Project, Oxford University,

www.kafkaarchive.ox.ac.uk/letters/milena-1919.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2025.

This citation identifies both the translator and the hosting institution. Transparency about mediation—who digitized, translated, or edited the text—preserves scholarly accountability.

Digital Archives and the Challenge of Provenance

Digital archives revolutionized access but complicated citation ethics. When a manuscript is scanned and posted online, multiple layers of mediation intervene between the original and the researcher: digitizers, metadata editors, institutions, and sometimes crowdsourced platforms. MLA style requires acknowledgment of each relevant “container” to avoid ambiguity.

Provenance and Authenticity

A key ethical issue is provenance: knowing where the digital item originates. Scholars must ensure that an online image or transcription derives from a legitimate institution or credible digital archive—not an anonymous website. MLA discourages citations to unstable or unofficial scans unless no better version exists.

Multiple Containers

Digital materials often exist within nested containers: an item (letter) within a collection (papers) within a digital database (e.g., Gale Primary Sources). MLA’s multi-container model captures this hierarchy:

Hughes, Langston. “Letter to Arna Bontemps,” 12 June 1936. Langston Hughes Papers, Box 23, Folder 4, Yale University Library, ProQuest History Vault, ProQuest, search.proquest.com/…

Here, Langston Hughes Papers is the first container, ProQuest History Vault the second, and ProQuest (the database provider) the third.

Metadata and Access Dates

Digital repositories frequently update metadata or URLs. MLA therefore recommends including the date of access for online archival citations. Though optional for stable sources like DOIs, it remains crucial for dynamic databases.

Ethical and Technical Issues

Citing digital archives also raises copyright and privacy concerns. Many collections digitize letters or diaries of individuals who never intended publication. MLA encourages writers to credit the holding institution prominently and avoid reproducing sensitive materials without permission.

Moreover, digital archives vary widely in format. Some provide image facsimiles; others, TEI-encoded transcriptions. In each case, citation should specify whether the version used is a digital facsimile, transcription, or translation.

Table 1 – MLA Components for Citing Archival Materials

| Item Type | Essential Elements | Digital-Specific Additions | Example (Simplified) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manuscript / Letter | Author, title or description, date, collection, repository | URL, access date if online | Dickinson, Emily. Letter to Susan Gilbert Dickinson, 1861, Amherst College Archives, acdc.amherst.edu/… |

| Translated Manuscript | Author, translator, item title, collection, repository | Translator credit, version details | Tolstoy, Leo. Letter to Turgenev, translated by A. Maude, Digital Tolstoy Archive, Moscow State U., Accessed 2025. |

| Unpublished Work (Draft, Notes) | Author, description, collection, location | DOI or persistent URL | Joyce, James. Draft of “Ulysses”, National Library of Ireland Digital Collections. |

| Curated Digital Collection | Author(s), item title, collection title, database, institution | Database name, stable link | “Letter from the Trenches,” Europeana 1914–1918, Europeana Foundation, www.europeana.eu/… |

Special Considerations: Manuscripts, Translations, and Hybrid Sources

Manuscripts and Drafts

When citing manuscripts or drafts, MLA recommends describing the material clearly—“typed draft,” “holograph,” “annotated proof.” These terms convey physical characteristics relevant to textual analysis. In a digital context, this description also helps distinguish multiple versions of a work.

Plath, Sylvia. Draft of “Lady Lazarus,” ca. 1962, Box 12, Folder 7, Sylvia Plath Papers, Smith College Archives.

If accessed online:

———. Draft of “Lady Lazarus,” Digital Sylvia Plath Project, Smith College, digitalarchives.smith.edu/… Accessed 10 Aug. 2025.

Note how MLA’s structure remains identical; only the final element (URL + access date) differentiates the digital citation.

Letters and Correspondence

Letters are among the most cited archival materials. When both sender and recipient are known, MLA prefers the format “Letter to [recipient]” and includes the date. In edited volumes, an additional container (the book) follows.

If the letter is unpublished but digitized, the institution must be credited as the source.

Eliot, T. S. Letter to Ezra Pound, 18 May 1922, T. S. Eliot Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard U.,

hcl.harvard.edu/eliot/letters/1922/05/18. Accessed 9 July 2025.

Translations and Bilingual Editions

Digital archives increasingly include translated manuscripts. MLA’s ethics stress clarity about language mediation: always name the translator or editor, unless the translation is anonymous or machine-generated (in which case, note “automated translation”).

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Letter to Clara Rilke-Westhoff, 14 Oct. 1904, translated by Stephen Mitchell, Digital Rilke Archive, University of Munich, Accessed 2025.

If a translation appears alongside a facsimile, MLA suggests citing the specific version consulted e.g., “transcription” or “facsimile PDF.” Scholars should also respect the institution’s preferred citation model, often listed on the archive’s website.

Hybrid and Born-Digital Sources

Modern archives now include email correspondence, blogs, and digital drafts. Though not traditional manuscripts, MLA treats them similarly: describe the item type and repository.

Morrison, Toni. Email to Robert Gottlieb, 4 Sept. 1998. Toni Morrison Papers, Princeton University Library, digital.lib.princeton.edu/morrison/email/1998/09/04.

Such citations mark the evolution of what counts as “archival” in a digital age—where Word documents, emails, and tweets join handwritten pages as legitimate scholarly artifacts.

The Future of Archival Citation and Scholarly Integrity

The digital turn democratized access to archives, but it also blurred boundaries between primary and secondary sources. Digitized letters often appear in curated exhibits with editorial commentary, requiring scholars to differentiate between the item itself and the digital platform’s interpretation.

Transparency and Reproducibility

One of MLA’s core missions is reproducibility: readers should be able to retrace a scholar’s steps. In archival work, this means citing precise identifiers—box and folder numbers, item IDs, and persistent URLs. Where possible, scholars should note whether they consulted the digital facsimile or the physical original.

Ethical Use and Cultural Sensitivity

Citations also carry ethical responsibility. Digital archives increasingly include materials from marginalized or Indigenous communities. MLA’s inclusive approach urges researchers to credit source communities, acknowledge culturally restricted items, and avoid decontextualizing images or sacred texts.

For example, when citing Native American archival materials, MLA recommends adding an explanatory note such as:

“Accessed via the Plateau Peoples’ Web Portal, with permission of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.”

Such practices align with MLA’s broader commitment to decolonizing scholarship and respecting digital sovereignty.

Pedagogical and Technological Implications

For students, mastering archival citation teaches critical thinking about information layers: What is the original? Who digitized it? How stable is the URL? Teachers can use MLA archival guidelines to train students in digital literacy.

Technological innovations—such as Linked Open Data and persistent identifiers (PIDs)—are reshaping citation. MLA has begun integrating concepts like DOIs for manuscripts and ORCIDs for authors, bridging humanities and data science. Future editions may incorporate metadata citation standards, allowing scholars to reference not only documents but also dataset structures.

Preserving the Human Element

Despite digital efficiency, the essence of archival research remains human: the tactile connection to history, the act of deciphering handwriting, the emotional resonance of a personal letter. MLA’s framework honors that humanity by insisting on detailed, respectful citations that foreground creators and institutions.

Conclusion: Responsible Scholarship in the Age of Digital Abundance

As archives migrate online, the boundaries between reader, curator, and scholar increasingly blur. The MLA citation system offers a compass through this complexity, balancing traditional bibliographic rigor with flexibility for digital realities. Whether citing a medieval manuscript or an email, the scholar’s duty remains the same: to credit origins, ensure transparency, and preserve authenticity.

Digital archives have made it possible to explore the past with unprecedented immediacy. Yet, without proper citation, that past risks distortion. Each citation is therefore an act of ethical stewardship—a trace that allows future readers to verify, contextualize, and reinterpret knowledge.

By following MLA’s principles—clarity, accuracy, and respect for provenance—researchers contribute not only to their disciplines but also to the collective preservation of cultural memory. The task is not merely to cite the archive but to honor it, ensuring that even in a world of infinite copies, the uniqueness of every manuscript, letter, and human voice endures.