Academic writing has always been a tool for sharing ideas, but in the twenty-first century, how ideas are shared is just as important as what they express. With more research and learning taking place online, accessibility is no longer an optional consideration—it’s an ethical responsibility. The Modern Language Association (MLA) format, a cornerstone of academic communication in the humanities, provides a standardized framework for clarity and citation. However, in the era of digital scholarship, writers must look beyond aesthetics and citation correctness to ensure that their MLA-formatted documents are accessible to all readers, including those using assistive technologies.

This essay explores how to adapt MLA formatting to align with digital accessibility principles. It examines the philosophical and ethical roots of inclusive design, identifies common accessibility barriers in MLA-style documents, and provides practical solutions for writers, editors, and educators. In bridging traditional academic conventions with modern accessibility standards, we create a more inclusive landscape for scholarship—one that reflects not just knowledge, but equity.

Why Accessibility Matters in Academic Writing

Accessibility is often misunderstood as a technical requirement—a checklist of screen-reader tags, text contrasts, or alt descriptions. But at its core, accessibility is about communication. It asks: can every reader, regardless of ability, perceive, navigate, and understand the content equally?

The academic community depends on shared information. If a document excludes readers who are blind, visually impaired, dyslexic, or neurodivergent, it doesn’t just limit access—it weakens the integrity of scholarship itself. Accessible writing practices embody the principle of universal design: making communication usable for everyone, not just for those with disabilities.

In digital academic environments, this issue becomes urgent. Online journals, repositories, and learning management systems now host most research materials. Yet many MLA-style papers—PDFs, essays, theses—are not optimized for digital accessibility. Common errors include:

-

Inaccessible headings (improperly formatted in word processors)

-

Missing alternative text for images and charts

-

Poor color contrast in embedded visuals

-

Hard-to-read fonts or small font sizes

-

Improper hyperlink formatting

-

Overreliance on italics or color to convey meaning

While MLA provides guidance on structure, citation, and ethical sourcing, it does not directly address accessibility. Writers and institutions, therefore, must interpret and expand MLA principles to meet inclusive standards. Doing so not only ensures compliance with accessibility laws (like the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 508 in the U.S.) but also promotes fairness and clarity—the same goals MLA itself was designed to achieve.

Integrating Accessibility into MLA Structure and Style

Adapting MLA formatting for accessibility does not mean abandoning its conventions. Rather, it involves enhancing MLA guidelines with inclusive digital practices that ensure all readers can interact with the document effectively. Let’s examine the key elements of MLA style and how they can be reimagined for accessible communication.

1. Headings and Hierarchy

MLA papers traditionally use simple textual cues for hierarchy—title centered, section headings in title case, and no numbering. However, for screen readers, visual styling is not enough. Writers should apply true heading styles (Heading 1, Heading 2, etc.) in Word or Google Docs rather than manual formatting. This allows assistive software to recognize structure and navigate the document logically.

For example:

-

Accessible approach: Use “Heading 1” for the essay title and “Heading 2” for major sections.

-

Inaccessible approach: Bold or enlarge text manually without assigning heading levels.

2. Font and Readability

The MLA Handbook recommends an easily readable font, typically 12-point Times New Roman. However, accessibility best practices suggest flexibility:

-

Sans-serif fonts like Arial, Calibri, or Verdana are easier for many readers with dyslexia or visual impairments.

-

Avoid narrow, decorative, or script fonts.

-

Maintain consistent size (12–14 pt) and at least 1.5-line spacing for digital readability.

Writers should also ensure adequate contrast between text and background (a ratio of at least 4.5:1). Avoid light gray text, colored backgrounds, or overuse of italics, which can reduce legibility.

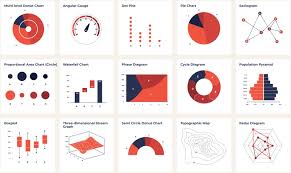

3. Images, Figures, and Alt Text

Visual elements—graphs, charts, or artwork—require alternative text (alt text) so that screen readers can describe the image to users. The alt text should summarize the visual’s purpose, not just its appearance. For instance:

-

Poor alt text: “Graph of data”

-

Better alt text: “Bar graph comparing student engagement rates across three learning platforms.”

In MLA-style documents, captions for figures should remain beneath the image, as the Handbook dictates, but writers can embed descriptive alt text in the document metadata. This preserves MLA’s visual format while ensuring screen-reader accessibility.

4. Hyperlinks and Digital References

In digital academic writing, URLs and DOIs often appear in the Works Cited list. According to the 9th edition of the MLA Handbook, hyperlinks should remain live and unstyled (no underlining or color changes). However, accessibility guidelines add two further requirements:

-

Hyperlink text must describe the destination, not just display the raw URL.

-

Example: Instead of “https://mla.org,” write “Modern Language Association website (https://mla.org).”

-

-

Links should open in the same window to avoid disorienting users with screen readers.

By combining MLA accuracy with digital clarity, hyperlinks become tools for navigation rather than obstacles.

5. Tables and Data Presentation

Tables present a particular accessibility challenge. MLA formatting allows tables to display data compactly, but in digital contexts, every table must be readable by assistive technology. The key is semantic markup—defining header rows and ensuring a logical reading order.

The following table contrasts standard MLA formatting with accessibility-enhanced MLA design:

| MLA Element | Traditional MLA Practice | Accessibility-Enhanced Practice | Accessibility Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headings | Bold text or title case only | Use built-in heading styles | Enables screen reader navigation |

| Fonts | 12-pt Times New Roman | Sans-serif, 12–14 pt, high contrast | Improves legibility |

| Images | Caption below image | Caption + embedded alt text | Describes visuals for non-sighted users |

| Hyperlinks | Plain text URLs | Descriptive hyperlinks | Clearer context for all users |

| Tables | Basic grid | Header rows tagged, no merged cells | Logical data reading order |

| Color/Contrast | Not specified | Minimum ratio 4.5:1 | Prevents readability issues |

| File Type | Print PDF | Tagged, accessible PDF or HTML | Preserves structure for assistive tools |

This table demonstrates how MLA formatting can evolve without losing integrity—each modification honors the spirit of MLA’s clarity while extending it to digital inclusivity.

Tools, Technologies, and Testing Accessibility

Designing accessible MLA documents requires awareness of digital tools that can identify and fix barriers. Fortunately, modern writing platforms already include built-in accessibility features—writers simply need to use them effectively.

1. Microsoft Word and Google Docs Accessibility Checkers

Both applications offer automated accessibility inspections:

-

Microsoft Word: Go to Review → Check Accessibility. The tool flags missing alt text, reading order issues, and heading inconsistencies.

-

Google Docs: Use the “Accessibility” menu (if enabled) to detect formatting errors and navigate headings easily.

These checkers help writers confirm that their MLA-formatted papers are structurally sound for screen readers.

2. Creating Accessible PDFs

When exporting MLA papers as PDFs, many writers lose accessibility layers. The key is to export from the source file (Word or Docs) using the “Create Tagged PDF” option. Tagged PDFs preserve headings, lists, and alt text. Alternatively, HTML versions can be hosted online for full compatibility.

Avoid “print-to-PDF” functions, which flatten the document and remove accessibility metadata.

3. Screen Reader Testing

Writers can test accessibility by using free screen readers like NVDA (Windows) or VoiceOver (Mac). Listening to the text read aloud helps identify navigation issues, unlabeled links, or missing descriptions. This process is not only technical—it cultivates empathy by allowing writers to experience their work as a reader with disabilities might.

4. Color Contrast and Visual Simplicity

Tools such as WebAIM Contrast Checker or Color Oracle simulate how color-blind users perceive content. By ensuring adequate contrast and avoiding color-only meaning (e.g., “see the red text”), writers make their MLA documents both ethical and effective.

Accessibility is never one tool or one format—it’s an ongoing practice of mindfulness. The combination of MLA structure and assistive technology ensures that form and function reinforce one another.

Rethinking MLA Through the Lens of Inclusivity

The Modern Language Association has long prioritized clarity, attribution, and scholarly ethics. Yet as academia evolves into digital spaces, the MLA framework must grow to embody inclusivity not just in citation ethics but in reader accessibility. Inclusive formatting is the next logical step in MLA’s commitment to intellectual transparency.

This does not require reinventing MLA—rather, it means interpreting its principles expansively. For example:

-

MLA’s rule of consistent formatting becomes an argument for consistent accessibility cues.

-

Its emphasis on acknowledging sources becomes an argument for acknowledging readers of all abilities.

-

Its value of precision extends naturally to digital precision—accurate metadata, logical hierarchy, and semantic structure.

Institutions, publishers, and educators can reinforce this approach by including accessibility guidelines in MLA workshops or citation handbooks. Just as students learn to avoid plagiarism, they can also learn to avoid exclusionary design. The ultimate goal is cultural: to redefine good writing as writing that is universally legible.

The intersection of MLA and accessibility signals a broader shift in academia—from authority to empathy, from standardization to participation. In accessible MLA writing, every reader becomes a potential collaborator, capable of engaging fully with the text.

Conclusion: Accessibility as the Future of Academic Communication

In the digital era, MLA formatting is no longer just about citations and margins—it’s about how knowledge travels across difference. Accessibility ensures that academic communication fulfills its ethical mission: the open exchange of ideas.

When a writer embeds alt text, checks contrast, or assigns headings properly, they are not merely complying with standards—they are extending an invitation to every reader. That invitation reflects the deepest values of scholarship: fairness, understanding, and curiosity.

As academia continues to globalize and digitize, the convergence of MLA and accessibility will shape the future of inclusive education. The ideal academic document is one that combines rigor of form with compassion of access—a text that speaks not just to experts, but to everyone.

In the end, accessibility is not a modification of MLA. It is its evolution—the natural next step in a centuries-long conversation about how to write clearly, cite ethically, and communicate responsibly in a world that reads in many ways.