In academic writing, every essay or research project depends on careful documentation of sources. For most students, the term Works Cited is familiar: it refers to the list of sources that have been quoted, paraphrased, or summarized within a paper. Each entry in that list provides the essential publication details—author, title, publisher, date, and other identifying information—formatted according to the Modern Language Association (MLA) style. The Works Cited page functions as a straightforward record of where information came from, allowing readers to verify claims and trace the intellectual path behind the essay.

An annotated bibliography, on the other hand, extends beyond simple documentation. It not only identifies a source but also provides commentary on it—an “annotation.” This annotation, typically a brief paragraph following the bibliographic entry, summarizes the content of the source and evaluates its quality, relevance, or usefulness to the research topic. While a Works Cited list merely points to a text, an annotated bibliography interprets it. It answers the implicit questions: What is this source about? Why is it credible? How does it relate to my project?

The difference may seem subtle at first, yet it has major implications for research practice. A Works Cited list demonstrates that the writer has supported their argument with evidence; an annotated bibliography demonstrates that the writer has understood and assessed that evidence. In this sense, an annotated bibliography bridges the gap between reading and writing, turning a set of references into a critical reflection on the body of scholarship that underpins a project.

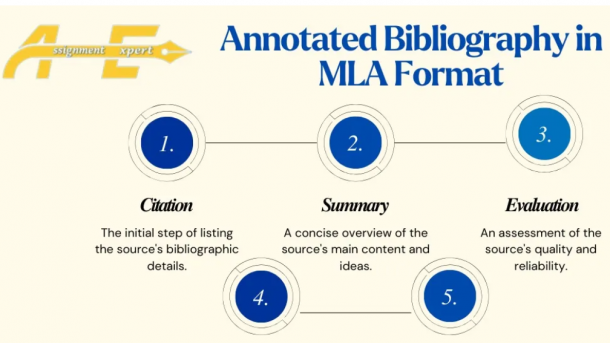

The MLA Handbook (9th edition) offers no rigid template for annotation length or style, since expectations vary across disciplines and assignments. However, most annotations range from 100 to 200 words and contain two main components: a summary that describes the source and an evaluation that assesses its credibility and significance. Understanding this dual purpose is crucial for crafting entries that are both informative and analytical.

Anatomy of an MLA Annotation: Description and Evaluation

An annotation begins where a normal citation ends. After listing the bibliographic information in standard MLA format, the writer adds a new paragraph—indented or aligned with the entry—that describes and evaluates the work. In print or online examples, this paragraph usually appears directly below the citation. For instance, a book citation would follow MLA’s familiar pattern: Author’s Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Publisher, Year. What follows is the annotation itself, which performs two distinct but complementary functions: description and evaluation.

The descriptive portion summarizes the source. It identifies the topic, thesis, scope, and key arguments or findings. The goal is not to reproduce the entire content but to distill its essence. For example, if annotating a book about climate policy, a student might write: “This book offers an overview of international environmental agreements since the 1990s, focusing on the Paris Accord and subsequent policy developments.” The summary should be objective, concise, and factual, avoiding personal opinion or excessive quotation.

The evaluative portion interprets or judges the source’s credibility, perspective, or relevance. This is where the writer shifts from neutral summary to analytical commentary. Evaluation might consider the author’s qualifications, the intended audience, the methodological rigor, or the way the source complements or contrasts with other materials in the bibliography. An annotation could therefore continue: “The author, a political scientist at Oxford, combines statistical data with policy analysis, offering a balanced but Eurocentric view. The book is particularly useful for understanding governmental negotiations but less helpful for grassroots perspectives.”

Together, description and evaluation turn a simple citation into a critical tool. The annotation shows that the student has read the source closely and can articulate why it matters. The language should remain formal and precise, yet accessible enough to communicate insight. Passive voice is acceptable but active phrasing often produces more engaging annotations. MLA style allows flexibility in tone, provided the entry maintains clarity and consistency.

The length of an annotation depends on the instructor’s requirements, but concision is valued. A paragraph of 150–200 words is usually sufficient. Sentences should flow logically from summary to evaluation, avoiding mechanical repetition such as “This source is useful because…” A more sophisticated approach integrates evaluation smoothly: “By providing a comprehensive statistical analysis, Smith’s article strengthens arguments about economic inequality and thus contributes valuable empirical evidence to my project.”

Unlike abstracts, which merely summarize, annotations involve judgment. Unlike reviews, they are not primarily opinion pieces but balanced reflections on utility and reliability. The annotated bibliography therefore occupies a unique space between summary and analysis, functioning both as a research log and as a miniature literature review.

Examples of Annotated Entries: Book, Journal Article, and Website

To illustrate how annotated bibliographies work in practice, it is helpful to examine examples of three common source types: a book, a scholarly article, and a web page. Each entry begins with a correctly formatted MLA citation followed by a concise annotation. These examples demonstrate not only the technical aspects of MLA citation but also the rhetorical strategies that make annotations informative and analytical.

Book Example

Hooks, Bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge, 1994.

Hooks explores how critical pedagogy can challenge systems of domination within classrooms. Drawing on her own experience as a Black feminist educator, she merges personal narrative with theoretical insight. The book argues for an engaged pedagogy that encourages both teachers and students to pursue learning as a liberating act. Hooks’ writing blends cultural criticism with pedagogical reflection, making the text foundational in feminist and multicultural education. Although first published three decades ago, its arguments remain highly relevant for understanding the politics of education. This source provides essential conceptual grounding for discussions of equity in higher education and helps frame contemporary teaching strategies within a social justice context.

Journal Article Example

Martinez, Raul. “Digital Resistance: The Politics of Online Activism in Latin America.” Journal of Media and Communication Studies, vol. 18, no. 4, 2023, pp. 215–233.

Martinez examines how social media platforms have transformed political mobilization in Latin America, focusing on case studies from Chile, Brazil, and Mexico. The article uses mixed methods—content analysis and interviews—to show how digital activism reshapes civic engagement. While the author acknowledges the risk of government surveillance, he argues that online spaces remain crucial for marginalized voices. The peer-reviewed status of the journal ensures academic credibility, and Martinez’s nuanced analysis highlights both the possibilities and limitations of digital protest. This article is particularly valuable for projects investigating social media’s impact on contemporary politics, offering empirical evidence to complement theoretical sources.

Website Example

United Nations Environment Programme. “Global Plastics Treaty: Progress and Next Steps.” UNEP.org, 2024, https://www.unep.org/global-plastics-treaty.

The web article provides a current overview of international negotiations concerning plastic pollution. Authored by an official United Nations body, it summarizes policy milestones, participant nations, and the treaty’s proposed goals. As an institutional publication, it reflects an authoritative yet diplomatic tone. The page is updated regularly, ensuring that data on environmental commitments remain accurate. Although it lacks critical analysis, the source is valuable for up-to-date factual information and serves as a reliable reference for environmental policy discussions. Its institutional credibility balances the subjectivity often found in news or opinion websites.

These examples illustrate the stylistic and structural norms of MLA-annotated bibliographies. Each entry adheres to the same fundamental pattern—citation first, annotation immediately below—but the annotations differ in voice and focus depending on the source type. The book annotation emphasizes theoretical contribution and relevance; the article annotation highlights research method and credibility; the website annotation stresses institutional authority and currency. Together they show that annotation style adapts to context while preserving MLA’s formal consistency.

To summarize the distinctions more clearly, the following table compares the typical features of a Works Cited list and an Annotated Bibliography in MLA.

| Feature | Works Cited | Annotated Bibliography |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Lists all sources used or quoted in a paper | Lists sources and adds a summary/evaluation for each |

| Content | Author, title, publication details | Full citation plus descriptive and evaluative paragraph |

| Length of Entry | Usually one line or short block | 150–200 words on average per source |

| Tone | Neutral, factual, purely bibliographic | Analytical, reflective, critical |

| Reader’s Use | Allows verification of sources | Helps understand content, quality, and relevance of each source |

| Function in Research | Provides documentation | Demonstrates comprehension and critical thinking |

This comparison underscores that the annotated bibliography transforms a static list into a dynamic tool for intellectual engagement. Where the Works Cited page concludes a paper, the annotated bibliography often begins one, guiding the researcher through the landscape of ideas before writing formally begins.

Strategies and Best Practices for Effective MLA Annotations

Creating an annotated bibliography is not only a mechanical task but also an exercise in critical reading and synthesis. Students frequently approach it as a mere formatting assignment, yet its deeper purpose is to foster intellectual dialogue between sources and researcher. To succeed, one must adopt a mindset of inquiry. Each source should be treated as a conversation partner, not merely as a citation.

When preparing annotations, coherence and tone matter as much as accuracy. The writing should flow naturally, connecting the bibliographic details to the discussion of content. Instead of introducing the annotation with formulaic phrases—such as “This article talks about”—writers can weave summary and evaluation into a single narrative paragraph. For example: “In this peer-reviewed study, Martinez explores the emergence of online activism in Latin America, revealing both the empowering and restrictive aspects of digital engagement.” Such sentences blend information with subtle assessment, allowing the annotation to read as part of a larger argument rather than as a detached note.

Instructors often emphasize objectivity, but a degree of personal evaluation is inevitable. The goal is not to declare whether a source is “good” or “bad” but to judge its appropriateness for the intended research question. An effective annotation shows discernment: it acknowledges strengths, limitations, and potential biases without dismissing the source altogether. When a source contains opposing arguments, mentioning them briefly demonstrates awareness of scholarly debate.

Formatting remains an essential consideration. The entire bibliography should be double-spaced, with hanging indents for the citation lines and standard paragraph indentation for the annotation. Font, margins, and headings follow MLA conventions: Times New Roman 12-point, one-inch margins, and a header with the writer’s last name and page number. Each citation begins flush left, and the annotation aligns with the citation rather than forming a new numbered section. Consistency across entries enhances readability and professionalism.

The process of writing annotations also helps refine a research question. As students summarize and evaluate sources, patterns of thought emerge: certain themes repeat, others conflict. These patterns reveal where scholarship agrees and where gaps exist. The annotated bibliography thus acts as a preliminary literature review, guiding the development of a thesis. It encourages depth of understanding before argumentation begins, helping writers avoid superficial or redundant references.

Beyond individual assignments, annotated bibliographies serve practical functions in academia and professional research. Scholars use them to keep track of evolving fields, librarians compile them to recommend resources, and grant proposals often include annotated lists to justify methodological choices. Mastery of this skill therefore extends beyond the classroom. It cultivates habits of precision, skepticism, and reflection that are essential to all intellectual work.

In evaluating sources, credibility should always take precedence over convenience. Peer-reviewed journals, university presses, and recognized institutions carry more authority than anonymous blogs or unsourced posts. When digital materials are used, MLA encourages the inclusion of access dates if the content is likely to change. Evaluative comments might address timeliness (“updated in 2024”), scope (“covers policy developments in three countries”), or reliability (“peer-reviewed and widely cited”). The best annotations integrate such observations naturally, showing that the writer has not only read but also assessed the source critically.

Finally, annotated bibliographies should demonstrate stylistic elegance as well as accuracy. Academic integrity does not preclude clarity or grace. A well-written annotation uses transitions to link ideas, avoids redundancy, and maintains a tone of measured analysis. It reflects both the writer’s understanding of the source and their command of academic discourse. When done thoughtfully, an annotated bibliography can stand as an independent scholarly product—an organized map of knowledge in miniature form.

Conclusion: From Citation to Reflection

The annotated bibliography represents the evolution of academic documentation from mere record-keeping to active critical engagement. In traditional research papers, the Works Cited page functions as the endpoint—a list of materials already used. In contrast, the annotated bibliography often serves as the beginning of research, charting the terrain before the final paper is written. Through its dual structure of citation and commentary, it turns the mechanical act of listing into a process of interpretation.

Understanding the difference between a standard Works Cited list and an annotated bibliography is fundamental. The former provides transparency; the latter demonstrates comprehension. Together they ensure both honesty and intellectual rigor. The summary component of each annotation trains students to read efficiently and identify central arguments, while the evaluative component fosters analytical thinking. In the age of information overload, these abilities are more important than ever.

The examples discussed—a book, a scholarly article, and a website—illustrate how MLA format remains consistent across media. Whether the source appears in print or online, the same structure governs citation, and the same expectation of critical engagement governs annotation. The comparative table clarifies that the annotated bibliography adds a new layer of meaning to the familiar mechanics of MLA documentation.

Ultimately, the value of an annotated bibliography lies not in its appearance but in its intellectual function. It compels writers to pause between reading and writing, to consider not just what a source says but how and why it says it. By articulating these reflections, students become more deliberate researchers and more responsible scholars.

The MLA format, with its emphasis on clarity, consistency, and acknowledgment of authorship, provides the scaffolding for this practice. Within that structure, the annotated bibliography becomes a space for curiosity and critique. It transforms research from a passive accumulation of references into an active dialogue with ideas. In this way, the annotated bibliography is more than a technical requirement; it is a bridge between knowledge and understanding, between citation and reflection—a bridge every thoughtful writer must learn to cross.